The local chapter of the Women’s Liberation Front (WLF) took off in Iowa City, Iowa, during the 1960s. A group working under WLF as the Publication Collective started writing a newspaper called Ain’t I a Woman (AIAW). They released about thirty issues from June 1970 to May 1974. Linda Jean Yanney’s (1991) oral history of feminism in Iowa City between 1965 and 1975 recounted numerous motivations underlying the creation of a local WLF chapter: restrictions on dorm life, absence of resources for daycare and health care, protests at Grinnell against exploitation of women in magazines like Playboy, civil rights, the need for self-defense training, and broadly the Vietnam War which prompted a student strike on campus in May 1970 following shootings of students at Kent State and Jackson State (60-67). The combination of these reasons to form a WLF, concretized by a list of demands in AIAW’s second issue, suggests membership emerged from many different parts of the community (“To Meet the,” 1970, 1). Although the WLF pushed against the University on several fronts, the address for AIAW in the first issue is the Jefferson Building (turned from a hotel into university offices by 1967). Moreover, WLF often collaborated with the University of Iowa’s Action Studies Program to host events. Communication studies scholar Kyra Person (1999, 158-173) and gender studies scholar Agatha Beins (2011, 16-23) celebrate AIWA’s impact by arguing it offered women without much access to print a chance to express themselves, challenged tendencies of the mainstream masculine and capitalistic press, and linked readers to networks with available resources across the country.

I suggest that feminists would benefit from reconsidering our approach to inclusion by carefully reading AIAW through a framework based on critical geography. Several reasons urge us to reapproach a feminist commitment to inclusion. For instance, Ahalya Satkunaratnam (2024), a critical scholar of dance, argues that “inclusion can often also feel like exclusion” because “it can disguise and uphold oppressive systems while producing positive, ‘feel good’ effects” (45). This tension animates many critiques for why inclusion often serves more as a hollow promise than a deep political commitment. While a full analysis of AIAW’s spatial politics exceeds the scope of this paper, I draw out a recurrent conversation about how geographical hierarchies precluded inclusionary politics to model an approach to inclusion rooted in space.

This essay argues that AIAW’s criticism of “metronormativity” when recounting their experiences traveling to New York City enables us to reapproach inclusion as the generative and restrictive forces of multiple, overlapping stories. Queer theorist Jack Halberstam (2005) conceptualizes “metronormativity” as a hierarchy that attaches safety to cities and devalues rurality (36-37). This hierarchy manifests in the places imagined as shelters for queer life and whose stories enter the histories of movements. Criticisms of metronormativity in a newspaper, which described itself at a few points as “a front for a world wide conspiracy of Radical Lesbians or the house cornfield of the Women’s Movement,” matter for more reasons than simply proving radical work happens outside urban centers (“Ain’t I a Woman,” 1970, 14). I suggest AIAW teaches us how to act inclusively by reckoning with biases that could fracture collective action and modeling a form of inclusion that emerges from attending to a multiplicity of stories.

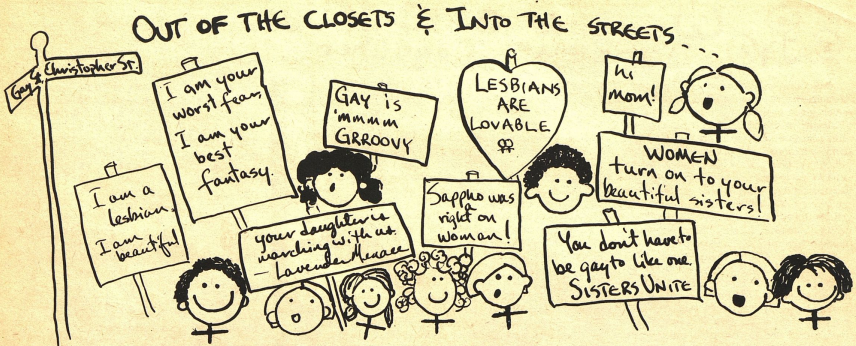

The third and fourth issues of AIAW demonstrate the Publication Collective’s attention to how geographical hierarchies restrict the development of radical politics. On June 28th, 1970, the inaugural Christopher Street Liberation March occurred to celebrate the first anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, often regarded as an accelerating event in the broader struggle against anti-gay and anti-trans violence. When the New York City Police Department attempted to raid the Stonewall Inn as they had done to numerous queer spaces, they encountered many fed-up trans and queer patrons who refused to follow orders by giving up their space (Hassoun 2023, 140-143). In an article titled as the chant “Out of the Closets & Into the Streets,” members of the Publications Collective penned small pieces about their experiences traveling to New York City. Broadly, we learn that the group attended workshops on lesbianism and feminism, shared a meal with members from the Daughters of Bilitis (an organization started in San Francisco to provide alternative spaces for lesbians facing raids), went to dances, and marched with thousands of people up Sixth Avenue to Central Park (“Out of the Closets” 1970, 11).

Reflections by members about the trip express a range of reactions that point to the messy politics of inclusion. Assuming anonymous authorship as the group often chose to do, one member recounted that the “All Women’s Dances … pointed out to us how differently we relate socially to each other in the midwest [sic]. We never dance with each other because there are no places in Iowa City where gay women can be together. It was so beautiful seeing women dancing with each other and meaning so much to each other” (“Out of the Closets” 1970, 11). Later issues of AIAW suggest that the group eventually found houses for parties that supplemented the lack of established venues.

Juxtaposed with this reflection about the radical feelings of intimacy often denied to gay women in Iowa City, two members reflected on another aspect of the group’s experiences. One writer highlighted the essentially passive-aggressive reactions they received during the trip: “When the sisters go to a meeting or something in a big city, and tell where we’re from, the reaction we get is: ‘My goodness, Iowa City! Isn’t that wonderful.’ (meaning: Wow, I didn’t think they had even heard about Women’s Liberation in Iowa.).” This reflection ended with the writer suggesting “we should have a conference and show’em how it’s done. But, of course, nobody from the East would come because they’d probably think all we’d do is pick corn.” The reflection even included a small emoji-like image of a corncob after the last sentence. Another writer arrived at a similar conclusion. People believed that “everything that’s ‘anything’ happens on the coasts. It’s the kind of myth that romanticizes those far away places and the people who live there.” She continued by describing the trip as “a high for us” because the group learned “that we’re struggling at pretty much the same levels as people from big cities” (“Big City, Little” 1970, 10). Both writers name an uneasiness with bias toward urban, coastal spaces. Scholarship tracking the development of urban queer politics suggests the consequences of metronormativity include “the ongoing commodification, corporatization, and de-politicization of the U.S.-based queer cultures in many locales” (Herring 2010, 16). Together, these reflections highlight a range of possible takeaways: the event offered new feelings of freedom in dance, failed to maximize the value of the time spent together, and fostered awareness of how coastal and urban biases shape the development of radical politics.

This trip to the Christopher Street Liberation March suggests a need to approach inclusion in action by both drawing out how geographical hierarchies create exclusions and how spatially approaching inclusion can move us in a more ethical direction. I turn to feminist geographer Doreen Massey’s (2005) scholarship to advance our thinking about inclusion in action. Whereas space often describes a genre of shared locations like schools, place pinpoints a location like the University of Iowa. Massey interrogates these terms to offer a slightly different perspective. She conceptualizes space as the constantly changing atmosphere, environment, and community formed from people intersecting with each other. Massey describes place “as woven together out of ongoing stories” and “as a particular constellation within the wider topographies of space” (131). The images of a weave and constellation suggest a sense of stability, yet the materials of each fluctuate. Fabrics fade, and our position between stars brings some constellations into sight and moves others out of view. Because “[t]here can be no assumption of pre-given coherence, or of community or collective identity” given space avoids homogeneity and is always under construction, Massey (2005) suggests scholars should interrogate how “the throwntogetherness of place demands negotiation” (141). Working with or alongside people inevitably creates tensions which should but do not always prompt reflexivity. The newspaper’s narratives about traveling to New York City embody this account of space and place because they forward an assortment of stories where the feelings of inclusion collide with feelings of exclusion. Writers in AIAW approached the same trip by offering stories containing new intimacies, stories about the value yet inefficiency of organizing marches, and stories about confronting the politics of where we imagine resistance happens.

These reflections of traveling to New York City do not necessarily tell us how to plan a better march, nor do they exhaust the complex conversations contained in the newspaper about what it means to publish or confront exclusions within feminist spaces. In fact, my essay misses the generative and messy tensions members of AIAW experienced as they reflected on Marxism and Leninism, race and sexuality’s influence on the WLF, a shared home where members lived and worked together, and the sheer exhaustion of producing a newspaper over time. Yet, the reflections in AIAW do illustrate a broader need to expand how we practice inclusion in action through a geographical lens. It is often not easily distinguishable whether a theory, action, event, or space is inclusive or exclusive. When confronted with the throwntogetherness of place and the frictions that arise between people with different aims or strategies for achieving them, we must resist the urge to stabilize or contain the telling of conflicting stories to manufacture stability. Instead, we should strive to think about inclusion as a multiplicity of stories that constantly pushes on our taken-for-granted hierarchies to produce more livable communities.

Note to Readers: You can find full copies of the newspaper Ain’t I a Woman through an open access database on Jstor (https://www.jstor.org/site/reveal-digital/independent-voices/aintiawoman-27953297/?so=item_title_str_asc).

References

“Ain’t I a Woman.” Ain’t I a Woman, October 30, 1970. Volume 1, Number 8.

“Big City, Little City.” Ain’t I a Woman, July 24, 1970. Volume 1, Number 3.

“Out of the Closets & Into the Streets.” Ain’t I a Woman, July 10, 1970. Volume 1, Number 2.

“To Meet the Needs of Women,” Ain’t I a Woman, July 10, 1970. Volume 1, Number 2.

Beins, Agatha. 2011. “A World Wide Conspiracy of Radical Lesbians: Ain’t I a Woman? and Lesbian Feminism in the 1970s.” Sinister Wisdom 82: 16-23. https://doi.org/10.5250/fronjwomestud.34.2.0186.

Halberstam, Jack. 2005. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York University Press.

Hassoun, Moussa. 2023. “From Protests to Pride and Back Again: New York Pride’s Origins and the Modern BIPOC Queer Movement to Reclaim it.” This Era of Black Activism, edited by Mary Marcel and Edith Joachimpillai. Lexington Books.

Herring, Scott. 2010. Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism. New York University Press.

Massey, Doreen. For Space. SAGE Publications.

Pearson, Kyra. 1999. “Mapping Rhetorical Interventions in ‘National’ Feminist Histories: Second Wave Feminism and Ain’t I a Woman.” Communication Studies 50 (2): 158-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510979909388482.

Satkunaratnam, Ahalya. 2024. “Inclusion.” In Rethinking Women’s and Gender Studies Volume 2, edited by Catherine M. Orr and Ann Braithwaite. Routledge.

Yanney, Linda Jean. 1991. “The Practical Revolution: An Oral History of the Iowa City Feminist Community, 1965-1975.” PhD Dissertation, University of Iowa. Proquest (9137011).