Are we Really ‘Born this Way’?

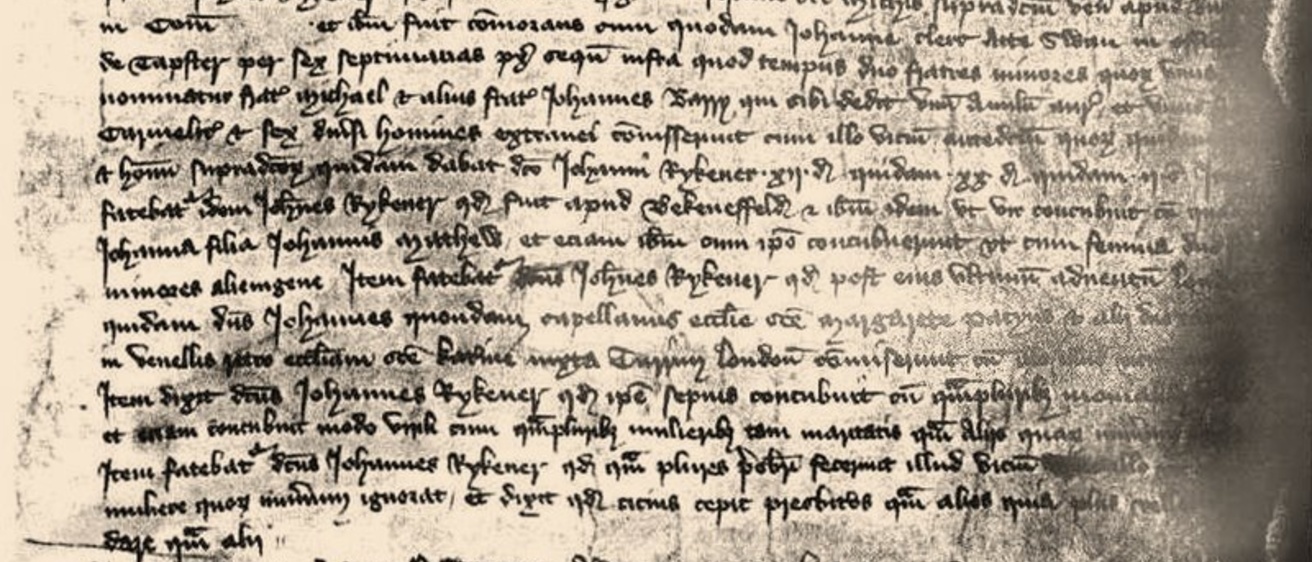

On December 11, 1395, Eleanor Rykener was questioned in a London court of law because she was living as a woman, despite her male biology. When asked why, the report states that, “a certain Anna, the whore of a former servant of Sir Thomas Blount, first taught [her] to practice this detestable vice in the manner of a woman. [She] further said that a certain Elizabeth Bronderer first dressed him in women's clothing.”[1] Undoubtedly, this is not the whole story, and it is filtered through a scribe who condemns Rykener’s sexual activity as detestable, a word Rykener likely did not use herself. Nonetheless, it highlights a transgender experience very different from the modern one. Increasingly, modern transgender and queer individuals describe themselves as being ‘born this way.’ Rykener’s statement suggests that her transgenderism was a communal creation and a choice, possibly her choice, but definitely other’s choice. As a subject, her identity, like that of many other medieval transgender individuals, is relational and follows Teresa de Lauretis’ and Linda Alcoff’s argument that subjectivity is created by “fluid interactions in constant motion and open to alteration by self-analyzing practice” (425)[2]. Gender, for many transgender medieval individuals that we have record of, is created by cascading and fluid moments of choice and creation.

The ‘born this way’ narrative suggests that the only way to be or have ever been queer is to have always been so. But this makes it nearly impossible to talk about queerness in the medieval period, where same-sex attraction and transgenderism was a matter of choice and circumstance, and not simply being. Medieval individuals, who in written accounts are frequently biological women living as men, rarely become men for gendered reasons. They do not declare that they have always been men, and they often decide to be men for the social benefits. Some of them even return to life as a woman. It is also important to note that none of these individuals ever declare themselves queer, at least in part because words like transgender and queer simply did not exist, and the terms that did exist do not express the concept I discuss here. But the lack of language does not mean the concept does not exist. For this reason, I follow Alicia Spencer-Hall and Black Gutt’s lead and use the term transgender, even though transgender carries many connotations that do not fit very well into the medieval period.[3] Acknowledging that queerness in the medieval period is very different from modern queerness, and that queerness may be fluid and a choice rather than a matter of birth, uncovers aspects of queer history that would otherwise stay hidden and opens up what being trans and queer can mean in the modern day.[4]

One common medieval reason for being transgender is that an individual is put into a situation they are unable or unwilling to perform in their current gender. In the romance Yde et Olive, Yde (initially female) dresses as a man when his father attempts to marry him. St. Matrona of Perge, St. Euphrosyne, and Juana de la Cruz Vázquez y Gutiérrez run away to monasteries to escape overbearing husbands (or the possibility of such). St. Marinos’ father decides to join a monastery, and so as to not be abandoned, Marinos begs his father to let him dress as a boy and come as well. Some of these individuals will retain their maleness despite hardship until the end of their life, some will not.

Another popular reason is that someone else decides it will be so. In The Romance of Silence, Silence’s parents declare their biologically female child male because of the king’s recent decree that women cannot inherit. If I may be so bold as to include Joan of Arc in this list, Joan said that it was God who commanded her to dress in men’s clothes and go into battle. Rykener could also fit into this category.

These latter cases tend to be fairly complicated. After some debate, Silence chooses maleness, and knighthood specifically. Yet, though they do not consent to the reveal of their biology, it cannot be said with certainty that they are opposed to their transition to femininity and the life they have thereafter. Joan’s male clothing is a reoccurring point of conflict in her trial, and one that she is (mostly) adamant about maintaining. But she does not claim to be male. Although we know little about Rykener, of these three examples, she seems the most certain about her gender. She dresses and acts as a woman, takes a female name and pronouns, and maintains her femaleness even when questioned.

These individuals’ gender is not fixed at their birth, nor, importantly, over the course of their lives. When accused of sleeping with a woman, St. Eugenia tears open her clothes and reveals her breast, before returning to life as a woman. Silence and Juana also return to a public femininity, although Juana goes on to make many statements about her maleness. A view of queerness that necessitates fixity would say that St. Eugenia cannot be queer, especially in comparison to someone like St. Marinos who is also accused of sleeping with a woman and chooses to be kicked out of the monastery rather than reveal his biology. Jack Halberstam sees “embodiment as a series of ‘stopovers’ in which the body is lived as an archive rather than a dwelling.”[5] Halberstam’s vision of queerness allows doubt, change, and fluidity. The end, or the beginning, need not define everything in between.

Marquis Bey’s comments on the ‘born this way’ narrative were what first allowed me to articulate the ideas I’ve put forward here. Bey argues, “I in fact do not believe that I, or anyone, is born any particular way, if that is to be taken as having some legible innate desire or identification preexistent to and independent of the ways we are socialized, the language available to us, the other entities we have to interrelate and thus emerge in the world with and through.”[6] This echoes Simone de Beavoir’s “one is not born, but rather becomes a woman.”[7] The ‘born this way’ narrative is powerful, but it cannot be the only one, not only because it erases queer history but because it limits modern queer experience. Bey’s queerness is created over time through relationships, community, language, and choice, and considering medieval queerness as a messy tangle of relationships, social circumstances, and choice provides a more complex view of queer history and the opportunity to open up what queerness can mean today.

Works Cited

Alcoff L. Cultural Feminism versus Post-Structuralism: The Identity Crisis in Feminist Theory. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 1988;13(3):405–36.

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Jonathan Cape, 2009, 273.

Bey, Marquis. Cistem Failure: Essays on Blackness and Cisgender. Duke University Press, 2022, 17.

Halberstam, Jack. Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. Oakland, University of California, 2018, 24.

“The Questioning of Eleanor Rykener (also known as John), A Cross-Dressing Prostitute, 1395.” Translated by David Lorenzo Boyd and Ruth Mazo Karras. Fordham, 1998, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/1395rykener.asp).

Spencer-Hall, Alicia, and Blake Gutt, editors. Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography. Amsterdam University Press, 2021.

[1] Translation by David Lorenzo Boyd and Ruth Mazo Karras. The original Latin is: “Anna, meretrix quondam cuiusdam famuli domini Thome Blount, primo docuit ipsum vitium detestabile modo muliebri exercere,” (https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/1395rykener.asp).

[2] Alcoff L. Cultural Feminism versus Post-Structuralism: The Identity Crisis in Feminist Theory. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 1988;13(3):405–36.

[3] Spencer-Hall, Alicia, and Blake Gutt, editors. Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography. Amsterdam University Press, 2021.

[4] I explore three genres, and thus three types of individuals. The first genre is romances, and the individuals therein are purely literary. The second is saints lives, which would have been read as true in the medieval period, but frequently had fictitious elements. Third is historical records, especially court cases, which detail historic individuals, including Juana de la Cruz Vázquez y Gutiérrez, Eleanor Rykener, and Joan of Arc.

[5] Halberstam, Jack. Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. Oakland, University of California, 2018, 24.

[6] Bey, Marquis. Cistem Failure: Essays on Blackness and Cisgender. Duke University Press, 2022, 17.

[7] Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Jonathan Cape, 2009, 273.