As a student affairs scholar-practitioner, I have dedicated my career to designing and researching college students’ leadership development experiences. Accordingly, I believe leadership development is a powerful way for students to explore, navigate, and disrupt the multiple, interlocking forms of domination, or what bell hooks refers to as the ‘white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.’ Increasingly, college students are leading social change and transformation efforts. Social change is not easy. While this post does not offer easy answers, I hope to offer some additional perspectives on college students’ leadership development and engagement. In what follows, I summarize and put two bodies of work in conversation: college student leadership development and feminist standpoint. If you are a student, I hope this piece resonates with you and gives you additional tools and language to further your leadership efforts.

Leadership has been conceptualized as both a process and an identity. The leadership identity development model explains how people explore and develop leader identities (Komives et al., 2006). A leader identity reflects confidence in one’s ability to engage with others to intentionally accomplish group objectives. As with all aspects of identity, leader identity development is influenced by intrapersonal (e.g., internal sense of self, values), interpersonal (e.g., interactions with peers, family), and contextual factors (e.g., systems of power, cultural traditions; Abes et al., 2007). Identity is explored and constructed in context. Others offer social location as a way of thinking about how one develops a sense of self, knowledge about oneself and the world, and considers power and capacity across contexts (Dugan, 2017; Levinson, 2011). In this context, leadership is both informed by and informs social location. Thus, continued leadership identity development requires on-going self-reflection and collective engagement, necessitating and complementing theorizations of leadership as a process.

Leadership, as a process, exists within and results from relationships among people (see, for example, Komives et al., 2013; Komives et al., 2017). The Social Change Model (SCM) of Leadership Development (Komives et al., 2017) is the most commonly used student leadership model on college campuses (Kezar et al., 2006). The SCM defines leadership “as a purposeful, collaborative, values-based process that results in positive social change” (Komives et al., 2017, p. 22). Importantly, the SCM details leadership processes at the individual, group, and collective level – challenging positional and hierarchical conceptions of leadership.

Recently, critical scholars have challenged the SCM for failing to critically interrogate power (Dugan, 2017; Museus et al., 2017). As a result of this critique, Museus and colleagues (2017) developed the Social Action, Leadership, and Transformation (SALT) model. The SALT model explicitly centers social justice while intentionally integrating the experiences of People of Color to develop a more capacious and power-conscious model. The SALT model offers several leadership elements: capacity for empathy, critical consciousness, commitment to justice, equity in purpose, value of collective action, controversy with courage, and coalescence (Museus et al., 2017).

Another approach to inclusive and transformational leadership is feminist leadership (Shea & Renn, 2017). Traditional college student leadership efforts often reinforce essentialist and binary gender constructions (e.g., Women in Business programs; detailing ‘women’s ways of leading’; Owen, 2020). Shifting from feminine to feminist leadership approaches recognizes all genders are constructed by powerful structures and seeks to subvert, rather than reinforce, oppressive structures. Feminist leadership relies on three connected tools: using and subverting power structures, complicating difference, and enacting social change (Shea & Renn, 2017).

Both the SALT model and feminist leadership recognize the value of lived experience and knowledge in engaging in leadership for social change and position leadership as consisting of individual and collective capacities. Thus, feminist standpoint theories offer useful theoretical and practical contributions to transformational leadership efforts. Feminist leadership tools and elements of the SALT model require critical consciousness to foster collectives committed to social change. In the SALT model, critical consciousness refers to understanding historical and contemporary systems of oppression and one’s positionality within these structures (Museus et al., 2017). Further, complicating difference involves challenging deterministic framings that position all women or all feminists as having similar perspectives and goals (Shea & Renn, 2017). Complicating difference requires both critical consciousness and boundary crossing to validate and recognize others’ priorities, values, and goals. Feminist standpoint theories can support these efforts.

Feminist standpoint theories assert that the social and political positions occupied by women and other groups who experience oppression can become sites of epistemic privilege because of both their individual and collective knowledge (Collins, 1997). Validating the knowledge of those who experience oppression incorporates valuable insight about how power works in society. In short, what and how people know is informed by their social and historical location (Harding, 1997). Thus, all knowledge is socially situated.

Just as it is important to recognize multiple feminisms, in order to challenge hegemonic white feminist perspectives, it is critical to recognize multiple standpoint theories. Standpoint theories have evolved through critiques and contributions from Women of Color. Collins’ (1990) Black Feminist Thought reminds us that every group’s knowledge is partial and unfinished. Thus, dialogue in diverse groups is the only way to approach the truth (Yuval-Davis, 2012). Standpoint theories do not seek to establish a ‘most marginalized’ group or a group as having the ‘truest’ knowledge. Rather, standpoint theories challenge dominant knowledge and provide analytical tools to understand the conditions marginalized groups face.

Leadership for social change must consider and center the multiplicity of knowledge. Engaging in struggle and subsequently developing standpoint uncovers the structures that reproduce injustice and inequality (Harding, 1991). In this sense, standpoint is co-constitutive of social change leadership efforts – as both require on-going investment, exploration, and struggle. Standpoint theories illuminate power structures, how and why differences exist among individuals and collectives, and validate traditionally marginalized perspectives. Such insights are central to leadership for social change.

An on-going commitment to critical consciousness is one way to reflexively engage with and foster knowledge via standpoint. Critical consciousness helps standpoint emerge, and through that emergence, differences can be identified, explored, and bridged. These efforts are central to leadership for transformation. In what follows, I offer several options for personal reflection, to encourage movement from theory to practice among student leaders.

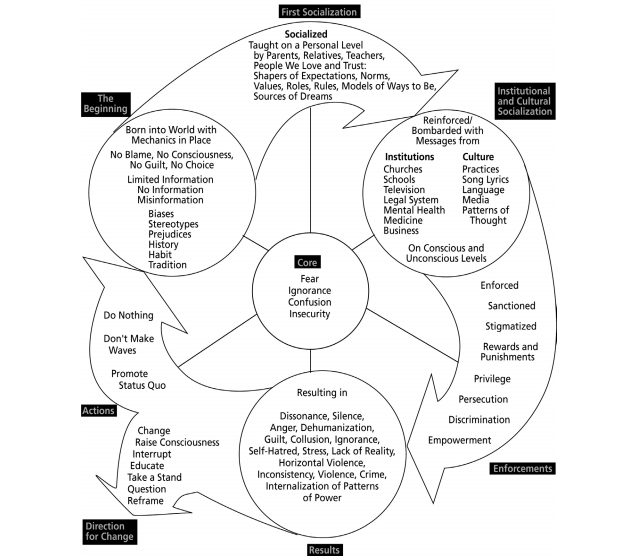

In integrating considerations of standpoint theories into leadership, I encourage personal exploration and reflection as a first step for feminist and socially just leadership. I do not offer personal reflection to conflate individual and group experiences, but to prepare individuals to recognize and explore the multiple, conflicting individual and group narratives that will likely emerge in leadership efforts. To move theory to tangible practice (or to engage in praxis), I suggest the following exercise. First, it is important to think about how your perspectives, beliefs, and experiences are situated within systems of power. Harro’s cycle of socialization illuminates how society often seeks to assign certain, unequal, roles or stories to us, as a result of our social location. While social location and standpoint are not the same, beginning with our social location is a practical tool for facilitating critical consciousness and standpoint. Although, it is important to remember that people with shared identities do not necessarily experience or make meaning of power in the same way. Further, our knowledge claims are also embedded in power.

Note: Adapted from Harro (2013).

After reviewing this image, think about how your identities, experiences, and ways of knowing can be traced through this model. The following reflection questions are intended to support this exploration:

- How would you describe your social location?

- What identities are important to you? How did you learn about these identities or how did they come to be significant to you?

- What historical and contemporary power structures shape your life? Your ways of engaging with the world?

- How does power inform your perspective on leadership? Are there particular moments or experiences that stand out to you when you think about this question?

As a college student, I used Harro’s model to explore my own socialization as a middle-class cisgender white woman in the context of the United States as a patriarchal and white supremacist society. This investigation helped me make connections between systemic power structures and my identities – increasing my critical consciousness and readiness to more intentionally collaborate with others. Middle-class whiteness was normalized in my upbringing, especially in the K-12 public schools I attended (e.g., dominance of white women as teachers, assumptions of economic resources engaging in extra-curricular activities) and in the media my family and I consumed (e.g., news stories that criminalized Communities of Color, TV shows that centered white middle-class people). Uncovering these connections helped me disrupt and notice the resistance I felt in recognizing the power and privilege afforded to me as a middle-class white woman and consider my incomplete knowledge of the world, particularly in relation to racism. As a student who wanted to engage in collaborative and social justice-oriented leadership efforts, it was important for me to recognize how my perspectives could disrupt or potentially reinforce power inequities. Illuminating connections between power structures and identities can facilitate critical consciousness and increased awareness of our inherently partial perspectives. Such efforts are essential for effective leadership and should inform our efforts to pursue social justice.

Notably, Harro’s model includes an off-ramp or ways to change the cycle. As informed by standpoint, social change leadership efforts can provide one avenue for disrupting unjust cycles and structures. You may join or generate movements, groups, and organizations that directly result from or contribute to your standpoint. Or, if your experiences are generally empowered, you may seek to be a co-conspirator. Regardless, the tools offered here are intended to facilitate critical consciousness as a foundation for articulating and challenging differences. Meaningful and on-going personal reflection, alongside engagement and struggle, can ensure that multiple standpoints are valued and central to transformational and feminist leadership efforts.

References

Abes, E. S., Jones, S. R., & McEwen, M. K. (2007). Reconceptualizing the model of multiple dimensions of identity: The role of meaning-making capacity in the construction of multiple identities. Journal of College Student Development, 48, 1-22.

Bowell, T. (2020). Feminist Standpoint Theory. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/fem-stan/

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

Collins, P. H. (1997). Comment on Hekman's Truth and Method: Feminist Standpoint Theory Revisited: Where's the Power?. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 22(2), 375-381.

Dugan, J. P. (2017). Leadership theory: Cultivating critical perspectives. Jossey-Bass.

Harding, S. (1997). Comment on Hekman's Truth and Method: Feminist Standpoint Theory Revisited: Whose Standpoint Needs the Regimes of Truth and Reality? Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 22(2), 382-391.

Harding, S. (1991). Whose science/Whose knowledge? Open University Press.

Harro, B. (2013). The cycle of socialization. In M. Adams, W.J. Blumenfeld, R. Castaneda, H.W. Hackman, M.L. Peters, & X. Zuñiga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice. (3rd ed., pp. 45-52). Routledge.

hooks, b. (2018). bell hooks on interlocking systems of domination. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUpY8PZlgV8

Kezar, A. J., Carducci, R., & Contreras-McGavin, M. (2006). Rethinking the "L" Word in Higher Education: The Revolution of Research on Leadership. ASHE Higher Education Report, 31(6). Jossey Bass.

Komives, S. R., Longerbeam, S., Owen, J. O., Mainella, F. C., & Osteen, L. (2006). A leadership identity development model: Applications from a grounded theory. Journal of College Student Development, 47(4), 401-418.

Komives, S. R. Lucas, N. & McMahon, T. R. (2013). Exploring leadership: For college students who want to make a difference (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Komives, S. R. & Wagner, W. (2017). Leadership for a better world: Understanding the social change model of leadership development (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Krantz, L., Fernandes, D. & Kohli, D. (2020). Amid a national reckoning on race, college students lead a push for change on campus. Boston Globe. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/06/26/metro/amid-national-reckoning-race-college-students-lead-push-change-campus/

Levinson, B. A. U. (2011). Exploring critical social theories and education. In B. A. U. Levinson, J. P. K. Gross, C. Hanks, J. Heimer Dadds, K. D. Kimasi, J. Link & D. Metro-Roland (Eds.), Beyond critique: Exploring critical social theories and education (pp. 1-24). Paradigm.

Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Museus, S., Lee, N., Calhoun, K., Sanchez-Parkinson, L., & Ting, M. (2017). The social action, leadership, and transformation (SALT) model. National Center for Institutional Diversity and National Institute for Transformation and Equity. https://lsa.umich.edu/content/dam/ncid-assets/nciddocuments/publications/Museus%20et%20al%20(2017)%20SALT%20Model%20Brief.pdf

Owen, J. E. (2020). We are the leaders we’ve been waiting for: Women and leadership development in college. men and leadership development in college. Stylus.

Shea, H. D. & Renn, K. A. (2017). Gender and leadership: A call to action. In D. Tillapaugh & P. Haber-Curran (Eds.), Critical perspectives on gender and student leadership (New Directions for Student Leadership, No. 154, pp. 83-94). Jossey-Bass.

Yuval-Davis, N. (2012). Dialogical epistemology – An intersectional resistance to the “Oppression Olympics”. Gender & Society, 26(1), 46-54.